Artist’s once ‘enchanted’ Prosperity home, studio has fallen into disrepair

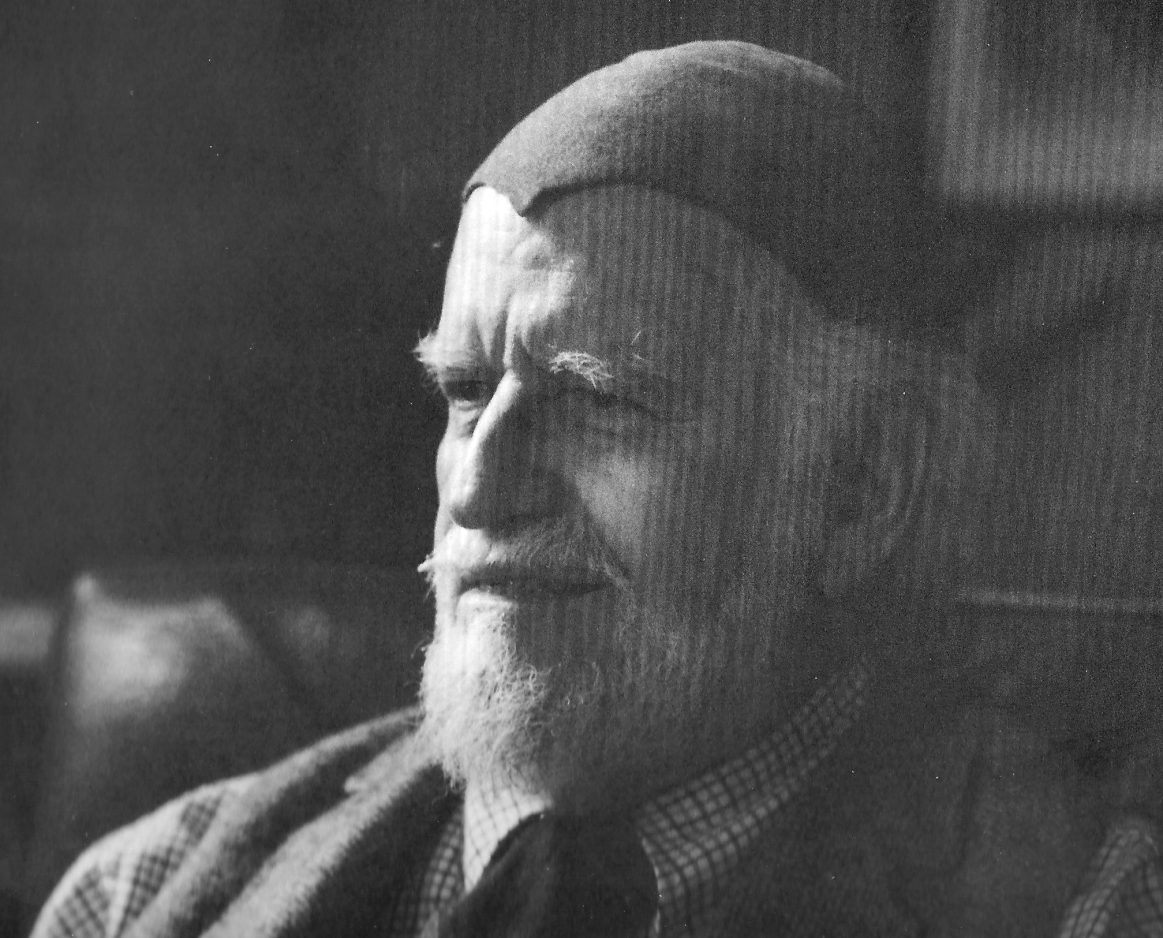

As a child in the first years of the 20th century, Malcolm Parcell played in an old log cabin atop a heavily wooded ridge a few miles south of Prosperity. In 1925, as a young man who had gained fame as an artist, he returned to that cabin to paint. He built on that cabin, one room after another, with rough-hewn beams and clapboard and stone, and called it “Moon Lorn.” And he would not leave it until his death in 1987.

“The place seems enchanted, as though it is a part of some long-ago yesterday. In some ways it is: the living record of a long career,” wrote Donald Miller in his 1985 book, “Malcolm Parcell: Wizard of Moon Lorn.”

The original cabin became a rambling house, a maze with small hallways and light splashing in from all directions. Parcell’s studio, an A-frame built in 1964, is positioned to take in northern light through a high clerestory, according to Miller.

The thick woods that surround Moon Lorn were captured in Parcell’s paintings, as were goblins and fairies darting among the trees.

Parcell reached acclaim as a painter in the early 1920s, where he studied and worked in New York. Primarily known as a portraitist, his paintings covered many subjects, and those depicting rural life and landscape around Moon Lorn are particularly prized by collectors and museums.

Sadly and shamefully, Moon Lorn today is abandoned and nearly a ruin. It has been ransacked by vandals, its plumbing and wiring stripped by copper thieves, its walls defaced by graffiti. Its doors and locks have been broken, its furniture and even a stained-glass window stolen. The floors are littered with beer bottles and trash.

After the artist’s death at age 91, Moon Lorn was purchased by the Malcolm Parcell Foundation. The foundation’s intent was to preserve the home and to use it as a residence and studio for artists who would maintain it. A decade later, however, the foundation was unable to continue attracting artists for that purpose, and Moon Lorn was sold in 1999 to Steven and Rosemary Rosepink.

The Rosepinks made several improvements to the property, drilled a new well and installed an above-ground pool for their children.

“There were lots of kids there,” said neighbor Steve Leonardi. “I called them serial adopters,” he added with a laugh. “It made me happy to drive by their place. There were always kids playing, and they had these big family gatherings with their older children and their kids. It may have surprised Malcolm how the place was being used, but I don’t think he would have minded it at all.”

Then Consol Energy expanded its planned longwall coal mining in the area and began purchasing property. In June 2014, the Rosepinks sold Moon Lorn, its 14 acres and mineral rights to Consol for $270,000.

According to Leonardi, vandalism of the property began last winter, and grass around the house grew chest high before being cut recently by someone appalled by the house’s condition. Intruders have ignored a wire stretched across the driveway and secured by a lock.

Brian Aiello, director of communications for Consol Energy Inc., said the company makes every effort to lease homes it purchases and have them occupied.

“We have in the past investigated potential partnerships with individuals and organizations who may have interest in restoring the property, and we will continue to do so,” Aiello said. “The property does sit within our future operational plan, so we will assess the appropriate time to engage in such conversations with those who may have interest in partnering.”

Aiello said Consol was unaware of the vandalism to Moon Lorn and that a contractor would be assigned to secure the property. Since then, the studio door has been locked and most doors to the house locked or covered by plywood, but several windows are broken and remain open, including a ground-level one offering easy access to the studio.

Sandy Mansmann, coordinator for the Washington County History & Landmarks Foundation, is a member of the Malcolm Parcell Foundation and was a dissenting board member when the house was sold in 1999. She has lately been gathering support and advice on how to preserve the structures on the property and get protective designation on the National Register of Historic Places.

Of Moon Lorn’s present condition, Mansmann said, “It’s not beyond repair, but we are close to losing it.”

More could be lost than the house. Surface subsidence from future longwall mining could destroy two archaeological sites on the property. According to Kira Heinrich, a historic preservation specialist with the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, the sites, recorded in the mid-1990s by members of the Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology, span several eras of prehistory and could contain features that would make them eligible for listing on the National Register.

Many have expressed dismay at the condition of Moon Lorn. Farley Toothman, former Greene County judge, remembers being taken there by his father as a boy to meet Parcell.

“I did tell Consol that if there isn’t a group that wants to possess it, and if Consol will lease it, I would fix it, restore it, cherish it, use it personally and share it, without being a pain in their neighboring industrial use,” Toothman wrote to Mansmann in an email. “I’d be there mowing the grass and putting windows back in next week if they’d let me.”

Stacy Phillips also recalls visiting Moon Lorn as a child in the 1970s, ascending the road up from the Day Covered Bridge. He wrote, “The twisted old trees are creepy and compel you to look back as you pass by to make sure nothing is following you. As the road straightens, dips, then rises back up into the distant canopy, an opening in the trees to the right reveals a sunlit patch in the midst of a dark forest. Simultaneously, a sign hanging on a chain draped between two trees, a small expanse of lawn, low stone walls and then a multi-gabled white cottage come into view…”

Phillips’ first impressions of Moon Lorn are remarkably similar to those of many others, whose sentiments he also shares.

“While it’s still here,” he wrote, “intact and, most importantly, in the setting that defines what Moon Lorn is all about, such a sense of place and time should not be allowed to disappear from the landscape.”