Cicadas are coming, but they’ll be sidestepping this area

Hate cicadas?

Then be warned: millions of the red-eyed, large-winged insects are ending their 17-year spell underground and coming to the surface to bellow their mating calls, breed and die.

But if you live in Washington, Greene, Fayette or Allegheny counties, there’s no need to close your eyes, cover your ears and not leave your house until the cicada siege ends. They won’t be coming to a neighborhood near you.

At least not this time.

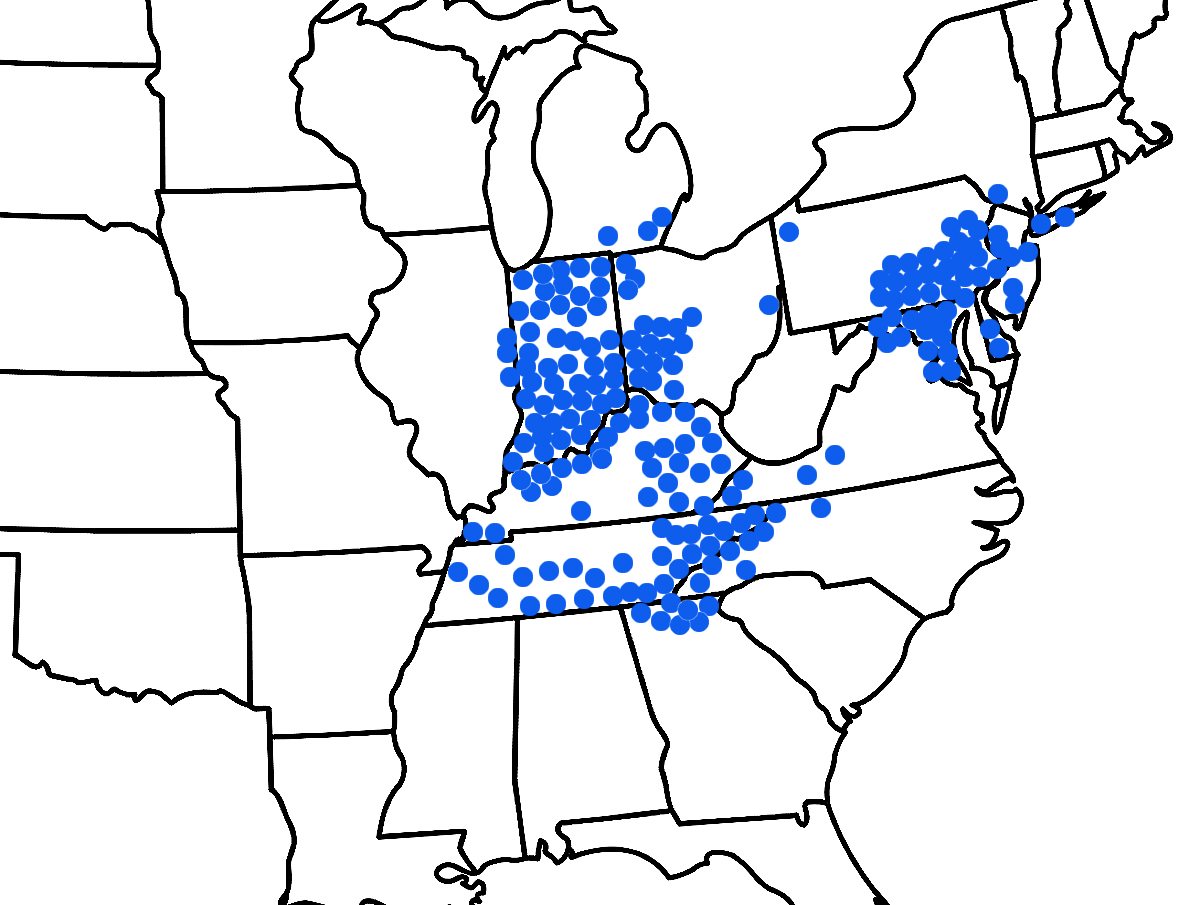

This is the moment when Brood X – the “X” is the Roman numeral “10” – emerges in a swath of states that includes Pennsylvania. But Brood X will primarily be confined to the central and eastern part of the commonwealth. The areas around Johnstown and State College are as close as Brood X will get to the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania. Brood X is, in fact, unevenly distributed around the eastern half of the country. Along with Pennsylvania, millions of Brood X cicadas have been or will be in emerging in Indiana, Maryland, Kentucky, Tennessee, a sliver of Georgia and the southern and central parts of Ohio.

“If people in Pittsburgh are looking for cicadas, they’ll have to go east,” said Gene Kritsky, a biology professor at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati, who has become known as “the Indiana Jones of cicadas,” thanks to his fascination with the critters.

Brood X is just one of 15 broods known to exist in North America today. For the most part, periodical cicadas emerge once every 17 years, though a couple of broods come out every 13. They’ve been doing this for at least 4,000 years. Their emergence has inspired literature and art through the centuries – cicadas turn up in Chinese folktales, and, more recently, the 1970 Bob Dylan song “The Day of the Locusts” was inspired by the wailing of cicadas near the Princeton University commencement ceremony where Dylan received an honorary degree. The cicadas were so loud that speakers at the ceremony struggled to be heard above the din.

It’s theorized that cicadas emerge on this precise timetable in order to outwit predators. After creating chimneys that they can travel through, they come out once the soil reaches 64 degrees and a good soaking rain moistens the ground. Once they are mature, cicadas take flight and land in nearby trees. Then, they start wailing, and once they mate, they fall to the ground and die. Their carcasses end up littering the landscape, and become snacks for squirrels, birds and bats.

“We’re witnessing this amazing explosion of life,” said Vicki Dodson, a Baltimore-area artist who creates cicada art and is relishing the appearance of Brood X. “You come out, you sing a little song, you get lucky and you die.”

Even if Brood X will not be appearing in this corner of the world, Southwest Pennsylvania is not off the hook when it comes to cicadas. Brood VIII made its 17-year appearance in Washington, Westmoreland, Allegheny and a handful of other counties in the region in 2019, and will be back again in 2036; and Brood V, which is dominant in Southwestern Pennsylvania, the western panhandle of West Virginia and the southeastern part of Ohio, appeared on schedule in May and June in 2016, and will be back in 2033.

It was Brood V that caused Emily Petsko’s lifelong aversion to cicadas. A native of Fredericktown and a former reporter for the Observer-Reporter, Petsko remembers a cicada landing in her hair when she was in her backyard pool around the time she celebrated her eighth birthday in May 1999.

“All I could do in that moment was scream like a banshee,” Petsko said. “I don’t remember how it ended – maybe I eventually came to my senses and dunked my head underwater, or maybe my mom came and brushed it off. But I do know I’ve disliked the creatures ever since.”

Now living in Silver Spring, Md., she hasn’t seen any cicadas near her abode, but has heard they are abundant within a mile in any direction from Silver Spring’s downtown. Petsko has been avoiding parks and wooded areas to try to minimize her chances of encountering cicadas.

“I carry a silk scarf with me so that I can quickly conceal my hair beneath a babushka if the cicadas are swarming,” she said. “I almost ordered a beekeeper hat online but figured that might be a bit extreme.”

Dodson is on the other end of the spectrum from Petsko. The advertising design director at Baltimore Magazine, she has created designs centered on cicadas for posters, mugs and T-shirts. In recent days, she has relished opportunities to see them.

“I’ve just been really looking forward to it,” Dodson said. “It’s an unparalleled opportunity to appreciate nature. They’re really pretty when you look at them.”

Though cicadas have been coming and going for centuries, they have vanished from some parts of the country, and their population is thinned whenever trees are cleared or a patch of land is paved over for a sidewalk or parking lot. But when cicadas do appear, they shouldn’t be feared, Kritsky explained.

“They don’t spread disease,” he said. “They’re not going to sting or bite you.”